UNVEILING MAN RAY

With This Artist, It’s Never Just Black and White

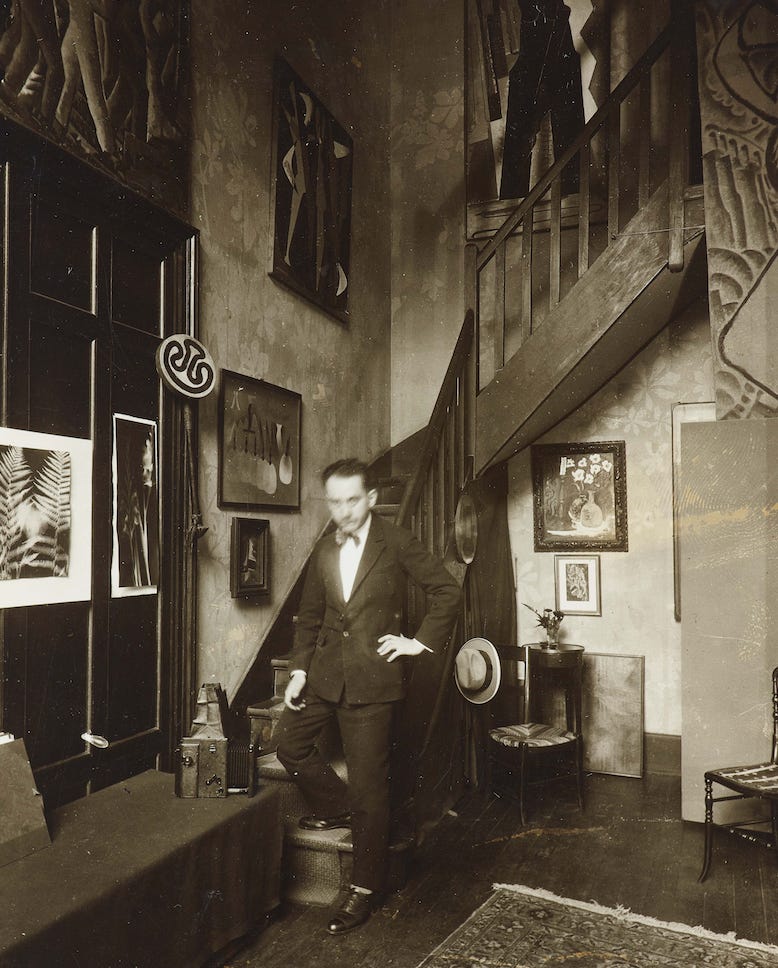

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976) Self-Portrait in 31 bis rue Campagne-Première Studio 1925; Gelatin silver print; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker,Photo by Ian Reeves © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

I'd heard of Man Ray before attending The Met's newest exhibition, Man Ray: When Objects Dream, but I really knew nothing about him, so I enlisted my friend, art historian and consultant, Larissa Bailiff to join and enlighten me. The exhibition displays 160 of Man Ray's works including paintings, objects, assemblages, drawings, prints, films, and photographs, meant to showcase the central role of the “rayograph” in artist Man Ray (1890-1976)’s boundary-breaking practice.

The only piece of art I'd ever seen of Man Ray's was a showstopping 1924 photograph entitled Le violin d’Ingres (which recently sold at auction for $12,400,000, the highest price ever paid for a photograph) and is featured in The Met's exhibition.

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976), Le violin d’Ingres, 1924. Gelatin silver print, 19 1/8" x 14 ¾ in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bluff Collection. Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker. Photo by Ian Reeves. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY/ADAGP. Paris, 2025.

The model is the artist’s girlfriend Kiki de Montparnasse, whom he posed, as Larissa put it, "as a languorous odalisque or harem figure in a turban, shown from behind with her curvaceous nude back augmented with the two black f-holes of a violin. This essentially transformed her body into an instrument, perhaps signifying that the artist saw Kiki as an object to be toyed with. The work turns on a clever pun, with the French word violin meaning a hobby (in addition to a violin), but also referencing the name of a 19th-century artist Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, who was admired by Man Ray. Famous for his sensuous nudes, Ingres’s well-known hobby was playing the violin. Originally, Man Ray painted the symbols onto the photograph, but eventually decided to re-photograph the overpainted version, thereby imprinting the instrument’s symbols directly onto Kiki’s back. “Here," Larissa explained, "Man Ray is disrupting the tradition of art through unexpected wordplay and darkroom techniques."

Larissa continued: " Some of us have a vague notion of Man Ray as a photographer, and more than a few of us assume that he was European. In a sense, the enigmatic artist was those things, but also not quite. Man Ray’s career was predominantly associated with Paris, and during the 1920s and ‘30s his income derived from work in the fashion industry and his black & white portraiture of celebrated European artists and literary figures. At the same time, however, the artist, born Emmanuel Radnitzy in Philadelphia and raised in Brooklyn, was also a multi-faceted visionary, an American Dada/Surrealist at the center of the Parisian avant-garde."

So, what is a "rayograph" (eponymously named by the artist)? Apparently, several months after his arrival in Paris, Man Ray, after inadvertently leaving glass equipment on top of unexposed paper in his developing tray in the darkroom, made an accidental discovery which led him to pioneer a new twist on a technique used to make photographs without a camera. By placing objects on or near a sheet of light-sensitive paper which he exposed to light and developed, Man Ray turned recognizable subjects into wonderfully mysterious compositions, leading his friend the Dada poet Tristan Tzara to describe them as capturing the moments 'when objects dream.’

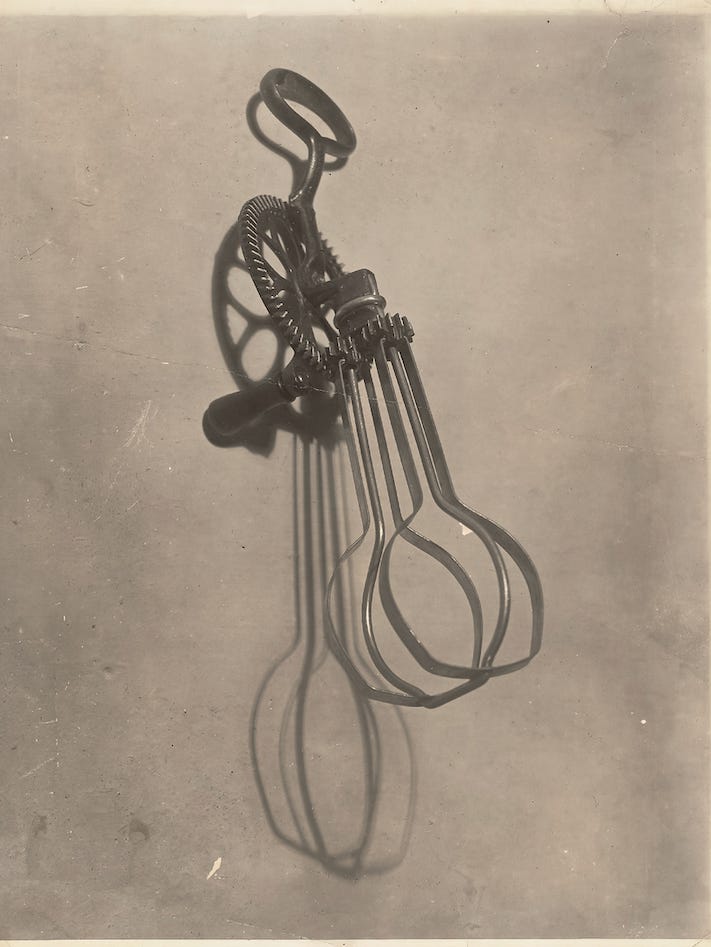

L’homme (Man) 1918–20, Gelatin silver print; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bluff Collection, Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker;Photo credit: Courtesy of The Bluff Collection, photo by Ben Blackwell © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

“It makes absolute sense that his rayographs would strike a chord with other experimental artists in Paris," said Larissa, "These works intersect with a modern interest in the abstraction and the transformation of everyday objects, while evoking a sense of whimsy and mysterious illegibility. Even the origin story of coming upon this technique by accident or chance (whether it really happened that way or not) – is so Dada.”

Man Ray could have eked out a meagre living as a more conventional painter but instead, during the mid-1910s, said Larissa, "he dove headfirst into the avant-garde currents swirling around his friend, the artist and provocateur Marcel Duchamp, most famous for his Dada “ready-mades,” including an actual urinal, which the Frenchman reoriented, signed (with a made-up name), and dated, in 1917, calling it 'The Fountain.' Compelled by such gutsy gestures, Man Ray changed his name, remade himself as a contemporary artist, and began creating his own radically disruptive objects, paintings, and prints, many of which have rarely been seen and are on display here.”

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976), Boardwalk 1917; Oil, wood handles, and yarn on wood; Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, acquired 1973 with Lotto Funds © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

"By 1921, Man Ray had divorced his first wife, a seeming requisite for living la vie bohème," said Larissa, "and relocated to Paris, to spend most of the remainder of his life. There he soon became a key figure in both the Dada and Surrealist movements. Explained Larissa, "Overlapping briefly in the 1920s, these modern movements each sought to shock bourgeois complacency and overturn concepts of tradition and rationality. Dada, which came first, was more centered on strategies of absurdity and nihilism, while Surrealism grounded itself in Freud’s notions of the unconscious. As Dada petered out in the mid 1920s, many of its artists moved over to Surrealism, and the boundaries between these movements were very blurry – in fact, one writer referred to the moment between the two as the movement flou – which means hazy, blurry, or out of focus."

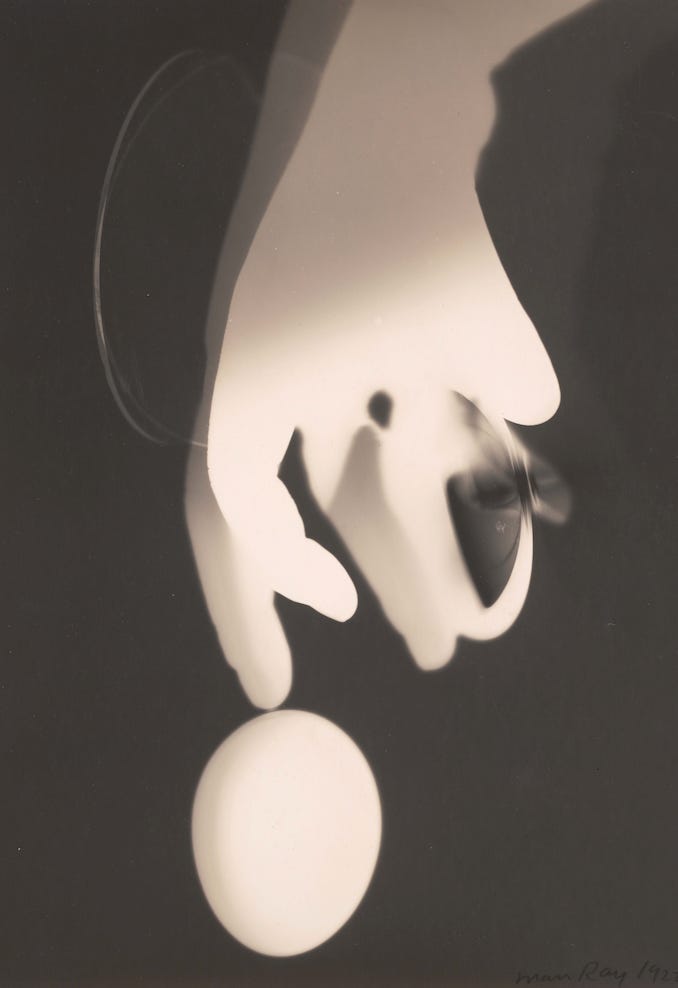

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976), Rayograph, 1922. Gelatin silver print, 9 ½ x 7 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bluff Collection. Promised Gift of John A. Pritzker. Photo by Ben Blackwell. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY/ADAGP. Paris, 2025.

Technically, Man Ray did not invent this mode of camera-less photography. William Henry Fox Talbot, Anna Atkins, and others in the 19th century had already begun putting objects and botanical specimens, on light-sensitive paper, to creating "photograms," as the prints came to be known. "But Man Ray re-invented this process," said Larissa, "manipulating effects, experimenting with accident, and creating startling uncanny compositions. In 1922, he shared 12 of his rayographs with the public, publishing them in a portfolio called Delicious Fields. The critics hailed this corpus for 'putting photography on the same plane as pictorial works' – or in other words, challenging the primacy of painting. Throughout the next several years, the artist would continue to experiment with his rayographs as well as other techniques and media."

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976), Rayograph, 1922. Gelatin silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Courtesy The J Paul Getty Museum, Lose Angeles. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY/ADAGP. Paris, 2025.

Beginning in New York, circa 1915, the exhibition spans several decades of Man Ray's career and,” said Larissa, "reveals an ongoing engagement with concepts of the cut-out, the everyday, contradiction, word play, morphology, desire, dimensionality, duration and movement.” Unfolding in a series of spaces that intersect with a central dramatic presentation of rayographs, the exhibition illuminates their connections with Man Ray’s other work in different media. All told, 60 rayographs are on display, more than have ever been seen together. A true boon for scholars, their breath also offers the lay person a chance to experience the true range of these photograms —some are of course more compelling than others — and to gage just how important this radical body of work was to Man Ray.” And, in fact, according to Larissa, “the rayographs–with their emphasis on shadows, blurring, transparency, and abstraction–influenced many subsequent artists and photographers.”

Other highlights to look out for: several mesmerizing solarization photos created while he and photographer Lee Miller worked and lived together from 1929-1932; a modernist chess set Man Ray designed in 1920 with a pyramid for the king, a cone for the queen, a rook in the form of a cube, and a knight inspired by the scroll of a violin; and a metronome disturbingly affixed with a photograph of singular beautiful eye that moves in time–which the artist titled Object to be Destroyed (1923) and provided with a set of instructions for its destruction. “

Man Ray: When Objects Dream will be at The Metropolitan Museum through February 1, 2026. And if you want to know much more about Man Ray. Larissa Bailiff conducts zoom classes on artsmuse,net every few weeks. The Man Ray Class will be held Tues. Oct. 7 at 5:30pm EST –OR– Wed. Oct. 8 at 7:30pm EST. If you can’t attend, sign up and watch the video at your leisure.

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976), By Itself I, 1918, Wood, iron, and cork LWL–Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Münster, Germany © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2025

Le violin d'Ingres....obviously the artist and his muse make beautiful music together ❤️